Gava Fox takes on the power of sport. And his ex wife.

You don’t have to be a sports fan to have been thoroughly engrossed by the recent Rugby World Cup in Japan, where the hosts won legions of supporters at home and abroad with a fairytale run before the tournament was settled by the traditional giants of the sport – with South Africa’s Springboks emerging triumphant.

I watched a couple of the games with my ex-wife, the pair of us displaying a degree of post-marital harmony rarely seen among divorced couples, and was reminded just how much sport can both divide and unite individuals, families, towns, cities and even countries.

The Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz famously wrote in the 18th Century that “war is the continuation of politics by other means”, an aphorism that could easily extend to ” … and sport is the continuation of war”.

The history of almost every ancient culture depicts people engaged in some form of sporting combat – with archery and wrestling a common theme across almost all of them – but you can go even further back and imagine to our Neanderthal ancestors and imagine teen brothers Ugg and Grugg messing around outside a cave entrance with a stone-tossing contest, or seeing who could throw a spear the furthest.

I’m pretty sure that’s where the shot putt and javelin were invented.

Pre-historic cave paintings from nearly 16,000 years ago in Lascaux, France, depict humans wrestling, as does rock art from Egypt dated back to 10,000 BC.

“The Epic of Gilgamesh”, considered the oldest surviving great work of literature, has the hero engaging in a form of belt-wrestling not dissimilar to sumo around 2,000 BC, while 500 years later the Greeks were taking part in bull-jumping competitions.

The ancient Greeks, of course, gave us the Olympic Games, with the first recorded gathering taking place in 776 BC.

The first games consisted only of sprint races, but four years later – yes, they were the ones who came up with the time interval – participants also competed in boxing, wrestling, jumping, javelin and discus.

Athletes competed in the nude to ensure there was no cheating, and art depicting the competition shows them to be less than generously endowed, as having a massive set of tackle in those days was considered low class and vulgar. I would have been royalty back then …

The games were considered so important that a general truce was enacted across all lands so that athletes could travel safely for the competition – and in any event, most of the competitors were drawn from the officer ranks of various armies.

Most early sport consisted of individuals competing for glory, but the first example of team games emerged in Persia, where cavalry warriors played polo to practice their synchronized horsemanship.

In 2002, shortly after the ousting of the Taliban following the September 11 attacks, I sat on a carpet on field in Mazar-i-Sharif in northern Afghanistan and watched two teams of mounted Tajiks take part in a game of Buzkashi – the first held for years, as the religious zealots had banned the sport as being barbaric. The Taliban really have no sense of irony.

I could have been transported back 2,000 years as teams of horsemen competed for the carcass of a decapitated goat, with the aim being to race around a flag at your opponents’ end before depositing the grisly prize at a stone cairn known as “the circle of victory”.

It was a brutal affair.

Riders whipped their horses, their opponents’ horses, and their opponents in the chase for the “ball” – and given you generally needed both hands free, you steered your mount by gripping the reins with your teeth, resulting in several incidents of unwanted dentistry.

Games can last for days in remote villages, but on this occasion proceedings were halted after a few hours. It was a goalless draw …

Two other team sports have survived in recognizable form from that period – hurling from ancient Ireland, and the not-dissimilar shinty from Scotland. For the uninitiated, both are a form of hockey – but the ball is mostly hit in the air, and the flailing sticks also means most participants have the smiles of an Afghan Buzkashi player.

It was actually from those British-ruled islands that almost all modern sport emerged.

The launch of the agricultural and industrial revolutions in 18th Century Britain gave people something they had never had before – leisure time – and they used the opportunity to invent a host of individual and team games most of which have not only survived, but spread across the world to become multi-billion dollar industries.

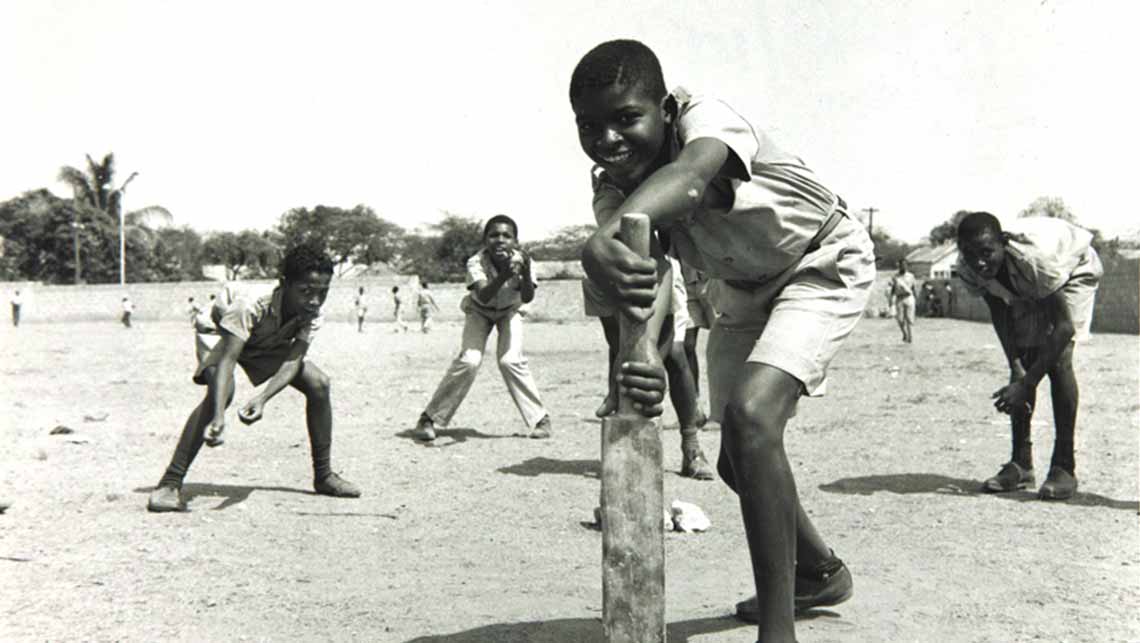

Football, cricket, rugby, tennis, golf, hockey … all of these emerged from the village greens or public schools of England, codified by a rigid set of rules before being exported across the empire.

“That’s not cricket, old boy” became an expression that signaled something improper was being done, something against the rules, while Henry Newbolt inspired a generation to fight in his poem “Vitai Lampada”, when in the heat of battle a young solider is spurred into action by his schoolboy memories: “His captain’s hand on his shoulder… play up! Play up! And play the game!”

The revolutionary Americans were one of the few colonies not to fully embrace British sports, although national pursuits such as baseball and NFL have obvious roots in cricket and rugby.

That sport became one of Britain’s greatest exports has, of course, been something of an albatross for the inventors as many nations not only embraced it, but became better at it and started beating the masters at their one game.

This happened at the same time another significant shift was taking place in sport – the advent of professionalism.

The owners of great industries in Britain took pride in pitting their workers against those employed by their rivals. Fabulously wealthy businessman would wager huge sums on the outcome of rugby and cricket matches between two mines or factories, but the problem was that the workers were not being paid to play – and they were expected to use their only day off to take part, or lose their jobs.

It started when cricket authorities realized they would lose a significant number of the very best players if they refused to pay them, so they came up with the idea of dividing them into “gentlemen”, or amateurs, and “players”, or professionals.

This form of sporting apartheid was so deeply entrenched that professional players were not allowed into the club house or to use other facilities, and when the first English teams containing professionals went abroad to play against the colonies, the gentlemen sailed First Class while the players went steerage – never socialising during the weeks-long voyages to India, Australia and South Africa.

Rugby took it further, and when coal miners and steel factory workers in the north of England were banned from the sport for life for accepting wages, they formed their own version of the game – rugby league – a hybrid that has 13 players on the field instead of union’s 15, and a modified set of rules.

The first cricket Test – a match between nations considered “proficient” in the game – was played between Australia and England in Melbourne in 1877, with the home team emerging victorious against the somewhat depleted tourists.

Incidentally, if you ever want to impress (or depress) your friends, ask them who played the first-ever international cricket match. The answer: USA versus Canada in 1844 at the St George’s Cricket Club in New York.

If England invented cricket, and Australia then created one of sport’s greatest rivalries by beating the masters in their own back yard in 1882 to start the Ashes, then India is now the rulers of all.

Although the fortunes of teams ebb and flow, cricket in India is on a scale that dwarfs the sport everywhere else it is played. Players earn millions of dollars playing various versions of the game and are worshipped as gods in a land not short of deities.

Still, of all sports, the money footballers make is, quite frankly, obscene.

According to Statista, Manchester United were the most generous employers in England’s premier league last season with an average annual salary of $8.6 million, while at lowly Cardiff the average wage was $1.4 million in the same division.

According to Forbes magazine, Argentine Lionel Messi is the highest-paid athlete in the world, earning $127 million a year – every year – for, ahem kicking a ball around a field.

In total 12 football players make the list of the top 100 highest paid players – each earning more than $25 million annually – with Cristiano and Neymar filling second and third place.

The highest paid athlete who is not a footballer is probably someone you’ve never heard of – the Mexican boxer Canelo Alvarez, while Roger Federer (tennis), Russell Wilson and Aaron Rodgers (American football) LeBron James, Stephen Curry and Kevin Durant (all basketball) fill out the top 10.

That Alvarez and Federer make the list is remarkable, because in terms of human achievement doing something on your own in sport is particularly laudable.

The world was mesmerized in the summer of 1954 when Roger Bannister first flirted with, then broke the four-minute mile.

Experts had said for years that it couldn’t be done, but if Bannister was to compete against current record holder Hicham el Guerrouj, he would trail in over 100 metres behind. The slender Moroccan ran the mile in 3:43:13 20 years ago and it is now one of the longest standing athletic records, although the event is rarely run, having long been superceded by the metric 1,500 metres.

Kenyan Eliud Kipchoge defied almost all scientific prediction in October when in a highly orchestrated run he became the first person to run the marathon (26.2 miles) in under two hours.

His 1:59.40 was nearly an hour faster than the first official record of American Johnny Hayes (2:55.18) – and considerably swifter than the soldier Pheidippides who, legend has it, ran from a battlefield near the town of Marathon in Greece to Athens in 490 BC to announce the defeat of the Persians.

Not quite the model of a modern day Olympian, he covered the distance in six hours before croaking “victory”, then pitched over and died.

Back to the rugby world cup.

I was watching the opening game of the 1995 competition with my girlfriend at a pub in London when South Africa were allowed into the tournament for the first time having finally scrapped apartheid. I’d had a rumbling stomach for a few days, which wasn’t helped by me leaping up every time the Springboks scored.

After the final whistle went, she dragged me to a clinic in our office where the nurse took one look at me and sent me directly off to London Bridge Hospital – an exclusive private establishment with rooms, as plush as any hotel, overlooking the Thames.

There I was examined and informed my appendix had burst, and rushed swiftly into surgery.

In the recovery that followed, the woman who was to become my wife – and then my ex-wife – helped nurse me back to health. In that time we watched a lot of rugby, and I’m proud to say I instilled in her a love for the game that has endured.

We were living in Kenya in 1999 and watched New Zealand thrash France in the first half of their semi-final. Thinking the game all but over, we drove from Naivasha to Nairobi to catch the last 15 minutes and witness one of the most remarkable comebacks of all time as French took victory. The 2003 tournament was another shared event, before we sadly went our separate ways.

After we watched a couple of games in the latest edition of the tournament, my ex returned to London but on the day of the final I received a text message from her saying she was watching in that same 1999 pub with friends – as I was, thousands of miles away.

Accompanying the text was a picture, her modest frame standing out from a burly crowd of white-clad England supporters.

She was wearing the same Springbok shirt I had bought her a quarter of a century ago.

Forget love, it’s sport that lasts forever.