Stephane Sensey’s images of Indonesia’s fisherman bring to mind the issues facing the oceans and those who depend on them, writes Stephanie Mee.

AS a nation of 17,000 islands, Indonesia has a symbiotic relationship with the sea. Nearly 6.5 million Indonesian people are directly employed in the fisheries sector and millions more depend on the ocean’s bounty for subsistence and survival.

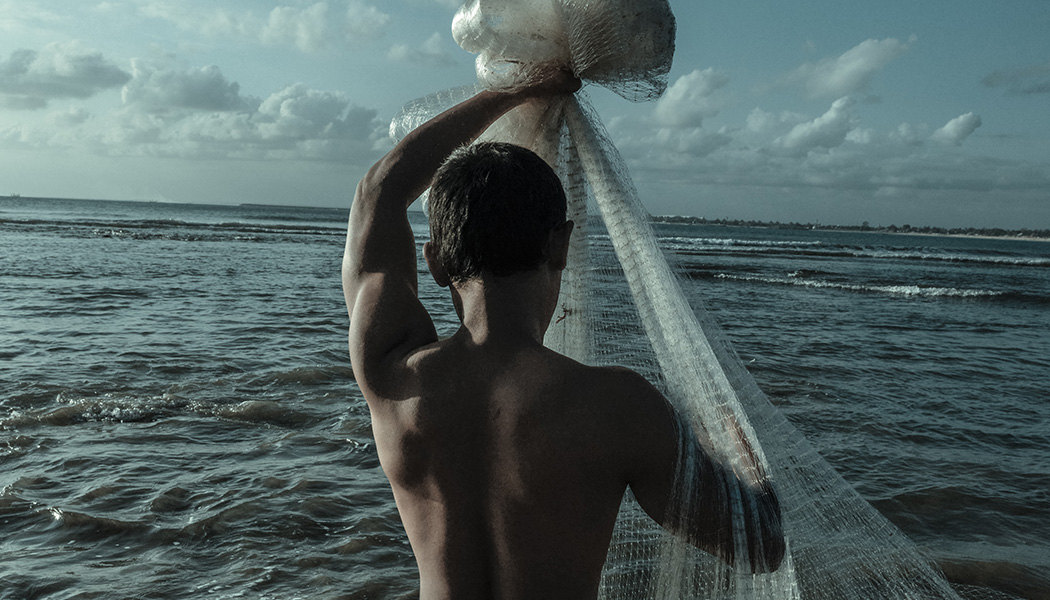

Fishermen ply their trade off the waters of nearly every island in the archipelago, and many use traditional methods that have been passed down through generations for thousands of years. Though their customs and catches may be different, they all share a close connection to the sea and rising concerns about the plight of their craft.

Stephanie Sensey has spent a considerable amount of time travelling around Indonesia’s islands and capturing images of fisherman scouring the seas. His photos come from places as diverse as Sumatra, Bali and Sulawesi, and through them he aims to portray and preserve the beauty of the ocean and the people whose livelihoods depend on it.

He says, “When I take photos my idea is to try to make a story and capture a feeling and a moment. Fishermen are interesting to follow and capture on film because for most of them this is an authentic tradition. It is an artisanal way to fish and part of their heritage. And I would say that most of them are doing it just to feed their families. None of them are rich; they are just surviving.

“For example the fisherman throwing the net was fishing in the same place and in the same way that his father and grandfather did. But while his father fished every day, he only does it once a week because he has another job. This is because there are less fish today, so he can’t catch as much as his father used to 20 or 30 years ago.”

Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing activities put considerable strain on natural resources and create unfair competition in the market. The Indonesian government takes harsh measures against IUU fishing, such as detonating and sinking foreign fishing vessels found trespassing and poaching in Indonesian waters, however, it is no easy task to police 2.8 million square kilometres of ocean.

While overfishing and poaching are depleting fish populations at a rapid rate, pollution is also taking its toll on both the quantity and quality of the fish and the fragile coastal environments where many of the fishermen live and work.

Stephane says, “People talk a lot about the problem of plastic in Bali, but it’s not just Bali. Everywhere you go – from Flores to Sumatra to Jimbaran – once you put your feet in the water you have plastic everywhere.

“I have this memory of travelling to Bangka Island too with one of the fishermen. From the distance the island looked amazing with all these granite cliffs that plunge into the sea, but when we arrived the beach was covered in plastic. This is a huge problem for the fish. How many fish must die because they have plastic inside their organs or wrapped around their bodies?”

To his surprise Stephane found that many of the fishermen he encountered were less concerned about money and more concerned about these pressing problems. He says, “Fishing is one thing, but respect for nature and the ocean is another thing. Of course the fishermen are concerned, but they cannot find a solution. They don’t have the education or the power, so I don’t even know if anyone will listen to them.”

Through this collection of images Stephane hopes not just to present a pretty picture, but also to inspire people to appreciate the sea and all the traditions surrounding it, and to raise awareness about marine conservation.

He says, “Yes, the scenery is beautiful, the people are beautiful, and the customs are beautiful, but it can all be lost in just a few decades. Let’s try and save this. Let’s educate and warn people of the consequences of taking massive quantities of fish out of the sea and of dumping massive quantities of garbage into the sea. Let’s try to respect what we have so that we can take the same type of images in another 30, 40 or 50 years.”