Depression is killing men at four times the rate of women. Gava Fox shares his experience of grappling with the black dog.

When Anthony Bourdain took his life in Paris earlier this year there was a worldwide outpouring of emotion that usually only accompanies the deaths of truly global icons, such as Princess Diana or Nelson Mandela.

His death was incomprehensible.

Handsome, intelligent and charming, Bourdain appeared to have it all. He was the man that women wanted to be with, and the man that men wanted to be.

He had a dark past, of course.

After starting as a dishwasher he moved up the culinary line to become a top chef, but it was his 2000 book Kitchen Confidential that changed his life and set him on the path to global celebrity. Witty and erudite, the book gave a never-before-seen insight into the workings of New York’s top kitchens, as well as chronicled his battles with addiction to drugs – particularly heroin.

The success of that book launched his TV career, and through the next decade and a half he fronted over 300 documentaries, starting as bog-standard cooking shows, but evolving into one of the most thoughtful travelogues to grace our screens.

Wealthy, successful and settled in domestic bliss with actress Asia Argento, what could have possessed him to fashion a noose in his Paris hotel room and kick away a chair from under his feet?

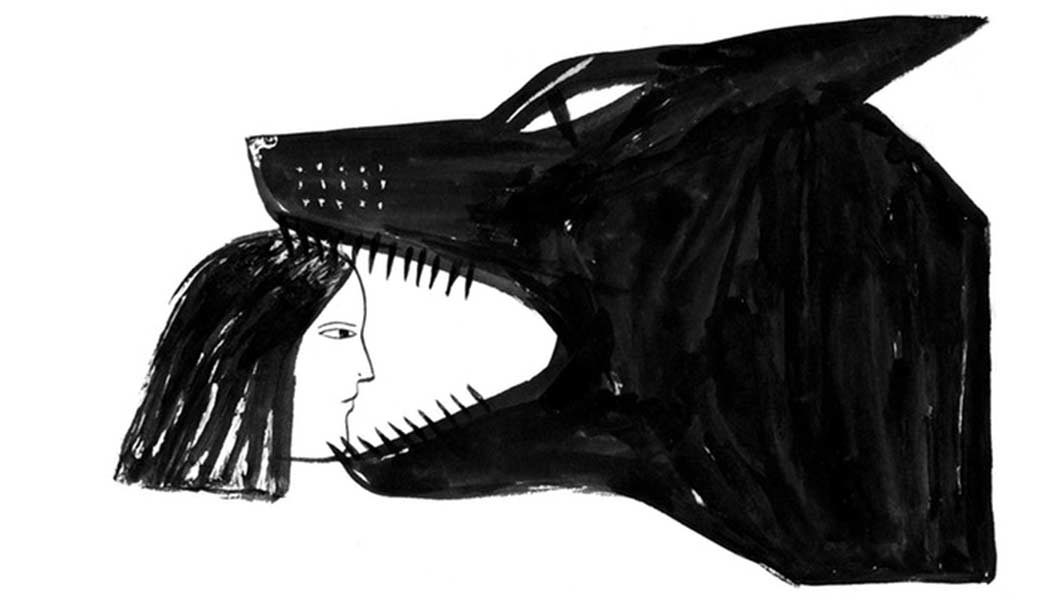

The black dog.

Winston Churchill is credited with popularising the phrase “black dog” to describe depression, but it is first mentioned in literature in 65 BC by the Roman poet and satirist Horace in a powerful description instantly recognisable to anyone who has suffered the blight.

No company’s more hateful than your own,

you dodge, and give yourself the slip; you sneak

in bed or in your cups, from care to sneak

in vain: the black dog follows you and hangs

close to your flying skirts, with hungry fangs.

The black dog followed Churchill for much of his adult life – frequently asleep in the corner, occasionally nipping at his heels and sometimes baying at the moon.

The older he got, the worse and more frequently it came. It would sometimes reduce him to spending days at a time in bed, drinking copious amounts of alcohol in a bid to escape the fug that descends on sufferers.

In bed he could do himself no harm.

“I don’t like standing near the edge of a platform when an express train is passing through,” he wrote in his memoirs. “I like to stand right back and if possible get a pillar between me and the train. I don’t like to stand by the side of a ship and look down into the water. A second’s action would end everything. A few drops of desperation.”

Those “few drops of desperation” will be recognizable to anyone who has ever felt the crush of depression – and most of us will feel it at least once over the course of our life.

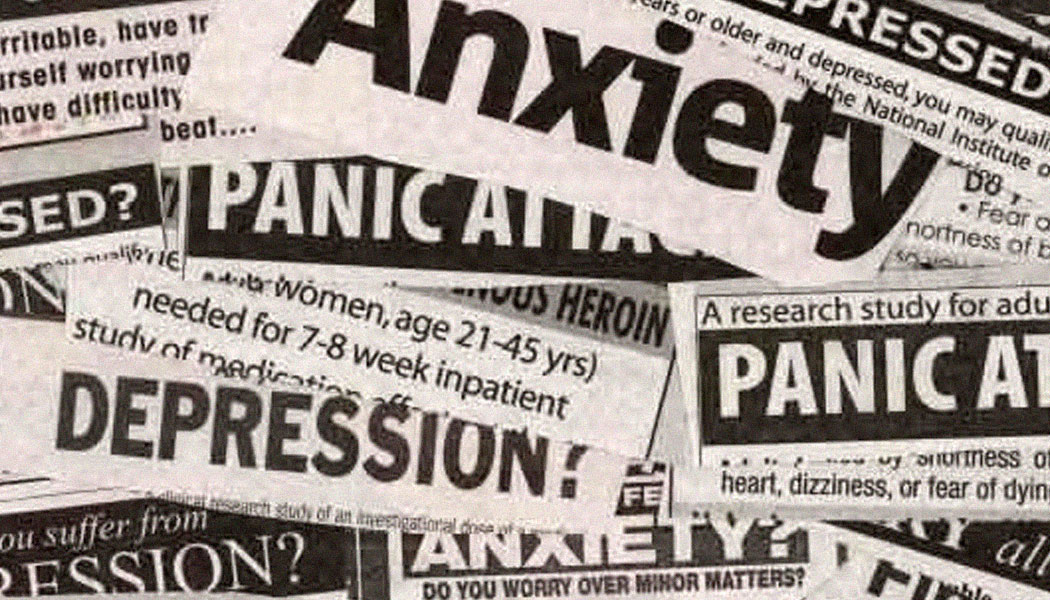

There is a great deal of misunderstanding about what constitutes depression and what causes it, but we do know what it isn’t.

It isn’t being moody or grumpy, or having a bad day, month or even year. It isn’t being unlucky, or tired or hyperactive or impotent or sexually ravenous. It isn’t being introverted, or manic, or lonely or alone.

But all or any of these can be symptoms of depression, and it’s time we spoke up about it.

“There is no point treating a depressed person as though they were just feeling sad, saying: ‘There now, hang on, you’ll get over it’,” wrote Barbara Kingsolver in The Bean Trees. “Sadness is more or less like a head cold – with patience, it passes. Depression is like cancer.”

This isn’t a cheery column, but in this edition I want to focus specifically on men’s mental health – not to diminish the seriousness we should attach to the genuine problems facing women, but rather because it is something I have felt personally, viscerally, and have seen in many of my male friends.

In every country of the world, women live longer than men.

This is for many reasons, but mostly it is down to our behavior. Men are more likely to engage in risky behavior, get into fights, battle wars, drive faster, drink more, smoke more and do more drugs than women. In fact, life expectancy for women is higher than for men in every country on the globe.

Tellingly, however, despite studies showing that women have suicidal thoughts more often than men, it is men who are more likely to act on them.

According to the United Nations World Health Organisation, global statistics show men are twice as likely to commit suicide as women – and in the West that ratio rises to four times.

In the past few years there have been several high profile cases similar to Bourdain.

Robin Williams, one of the greatest and most successful comedians ever, took his own life in 2014 after suffering from years of depression. The actor Philip Seymour Hoffman overdosed after falling into a depression caused by his fear of not being able to match his own high standards.

Closer to home, the brilliant Australian rugby player Dan Vickerman interrupted his international career to get a degree from Cambridge University, but took his life last year after finally retiring from the game.

If these immensely successful people, seemingly wanting for nothing, can get so lost in the throes of depression, what hope is there for the rest of us?

Take a look around you. It may be silent, but your friend, your brother, your father or your lover could all be in that situation.

It could be you.

My first taste of depression came just a few years ago, when I was in my forties, and lost my job of two decades because a slip of the finger sent an admittedly distasteful private electronic conversation to a far wider audience than intended.

In the months that followed, I withdrew almost entirely from social life – I calculated that at one point I went three weeks without speaking to another person. Family and friends who loved me and genuinely cared for me would telephone, but I wouldn’t answer. They’d follow their calls with messages and emails asking if I was OK, and those would be deleted without even being read.

It was a vicious circle. I wouldn’t answer one call because I was feeling utterly down. Then I wouldn’t answer the second because I would have to explain the first. It became this massive weight on my shoulders and the longer it went on, the worse it became.

I was too embarrassed to speak, too ashamed to admit how far down the road I’d gone, too humiliated to confess to my own insecurities.

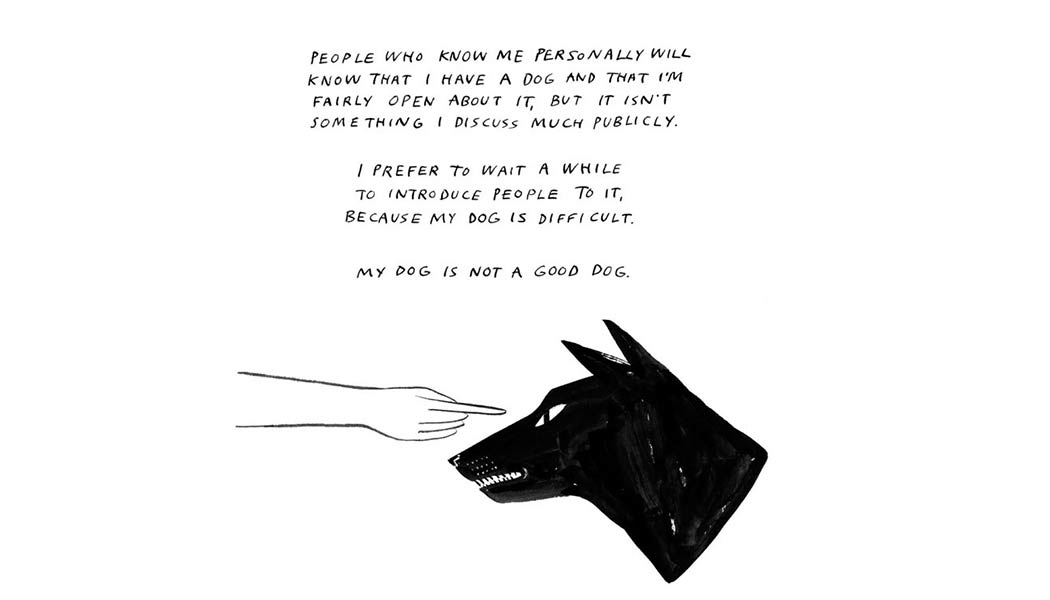

Two things pulled me back from the brink – moving to Bali and getting a dog.

The dog was a half-crippled mutt I plucked from the street, but an old friend keenly notes that it was “Streaky”, as I named her, who more rescued me than I her. The joy with which she greeted each walk and every excursion encouraged me to get out more. The unbridled affection she lavished on me every time I returned home showed me what unconditional love meant – even if I hadn’t recognized the same in those unanswered phone calls and emails from friends and family.

Moving to Bali gave me something else. On the Island of the Gods I discovered a few like-minded individuals who were prepared to talk about the issues that we faced. We’d meet up informally just to check on each other, to reassure one another that not being great was perfectly normal, but at least we should share it.

Things fell into place. A new job, a girlfriend, savings growing in the bank, everything going well to the point you forget just how bad things were – and you start taking life for granted.

Made redundant in a company downsizing, I felt myself sliding again towards despair. The black dog seemed more powerful than faithful Streaky, who lay at my feet imploring me to get up and get out. I became sloppy, and the next thing I knew I was arrested for possession of a small amount of hashish.

Conversely, being locked up in jail snapped me out of depression. Family, friends and even complete strangers rallied to make sure I was well looked after. In police remand cells, where I was held for three months, the environment was so raw, so hostile, and so mystifying that you had almost no time for introspection. Survival was everything.

It was only after moving to Kerobokan – the Big House – and finally aware of the sentence I had to complete, that I could reflect on my situation.

I was lucky. In prison I was surrounded by “lifers” – many clearly in need of urgent mental health care. Attempted suicides were commonplace, and someone was successful at least every month or so.

Still, I managed – inspired a great deal by Australian Matthew Norman, one of the “infamous” Bali Nine, who woke every day with the mantra “what can I do today to help someone else”.

Released after seven months I received great post-incarceration counseling including excellent instruction on Yoga and meditation that I still practice today.

Recently, more than a year on, I again found myself hearing the muffled growling of the black dog. Again I found myself not answering calls, not replying to emails, making excuses.

This time I felt I had far better coping mechanisms, and a more recent change of fortune will see me soon return to my old career.

So what should you do if you feel the black dog nipping at your heels?

Here are a few things you could try to set him back in the kennel:

Be sociable. This can be difficult particularly if you don’t want anyone else to know how you feel, but it can help. If you can, try to share what you are going through with a good friend.

Change your routine. Keep a diary, go jogging, surfing, cycling or golfing. Try yoga or get a dog and take it on long walks.

Don’t be afraid of the moment. When you’re having a bad day you shouldn’t spend it trying to repress the pain you’re feeling. Although it sometimes feels counter-intuitive, sometime it helps to acknowledge your feelings, even if only to yourself, and in doing so acknowledge that those feelings will pass.

Remember, it is ok to not be ok. But please share it with someone.

………………….

Enjoyed reading this article? Read more by the same author here.