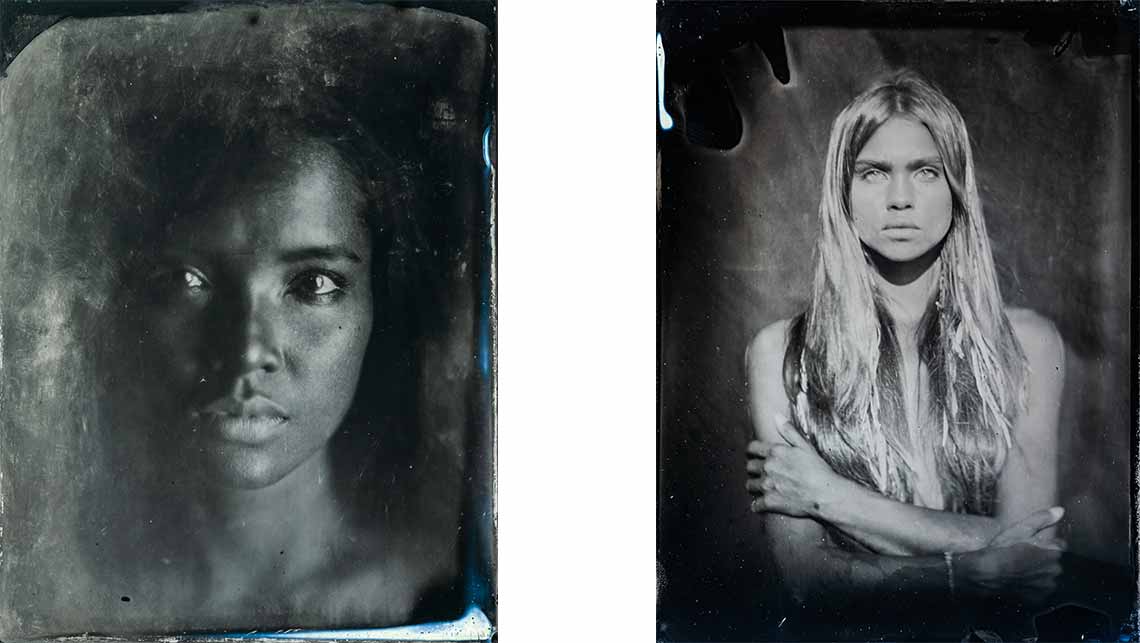

Photographer Stephan Kotas works with a hundred-year-old camera to produce complex works that bring the past alive.

Stephan, where on earth did you find a wet plate camera and what sparked your interest in this process?

I found the camera in Europe. It’s about 100 years old and it’s made from mahogany. It’s a very simple device, basically just a dark box with a lens. I had been shooting digital for more than 10 years and didn’t really care much about the history of photography or old techniques, but when I first came across the wet plate collodion process I was immediately amazed. The results are so beautiful and different from any other photographic technique. What struck me the most was that you can see the image come alive right in front of your eyes. It’s like magic. It’s one of a very few techniques where you can produce a positive image straight from the camera: there is no negative and each image is a one-of-a-kind object of art. More like a painting, actually. The process is fully hands on and involves working in a humid darkroom filled with chemical odor – about as far away as you can get from sitting comfortably in a cafe with your laptop.

Forget film, we’re talking about a technology that is seriously old … there must be some technical issues for you using it in 2020…

The wet plate collodion process dates back to 1851 and the very dawn of photography. Back then taking photographs, or ‘light painting’ as it was called, was the discipline of a very small number of people. They weren’t photographers or artists really, but inventors, chemists and scientists. Interestingly enough, the very first images, which are now almost 170 years old, still look the same as if they were taken yesterday. So yes, there are a few technical issues! This is a pure chemical process and nobody really makes photographic chemicals anymore, especially in Indonesia. I had to learn to mix my own chemicals, and re-make old formulas to match the tropical climate. I’m pretty sure I am the first ever photographer to successfully practice this technique in Indonesia.

How long do your subjects need to sit for a shot?

The wet plate film is very slow, which means its sensitivity to light is very low compared to modern cameras. Because of that the exposure times are also much longer. When you look at old images you can see that the people’s poses are very stiff. That’s because they had to hold still for a long time. The exposure depends on light conditions.

I shoot mostly with sunlight and it can vary from few seconds to about 20 seconds and even up to a minute. It’s hard for the model as well, and it’s not easy to get a sharp image. One of the unique things about wet plate film is that it only reacts to the UV light spectrum, which is why the images have a different look. The film reads colors differently. For example yellow is very dark and red becomes black. There is no light meter for UV light so you have to guess the length of exposure. It takes experience.

Tell us about the chemical process and how you go from shooting an image to producing a print?

First of all, before every shoot I need to mix all my chemical solutions. That’s a process on its own and you need to learn chemistry and lab safety. During the shoot itself there are several steps: first I take an aluminium plate and pour it with a mix of collodion and salts. Then I put the coated plate into a solution of silver nitrate. It’s the combination of these two chemicals that creates a light sensitive material, the liquid film.

From now on I need to work in the darkroom only under safe light. This film needs to stay wet (therefore wet plate) throughout the whole process until development otherwise no image will appear. That’s one of the reasons why it’s so hard to shoot in a tropical climate. After sensitising I put the film into the plate holder, place it in the camera and make an exposure (you need to have your model, framing, lighting etc. prepared beforehand). Then I rush back to the darkroom where I pour it with developer – that’s when you start seeing an image appearing on the plate. I have to stop the development in time to avoid overdeveloping it.

After that I put it into a fixer solution to wash off the unexposed silver. Then the plate needs to be washed in clean water and dried. It is then dried and I still need to do varnishing. That’s the final coating of the image to seal it off from air. After that the image will stay as it is for hundreds

of years.

Do you have any friends who are Milennials? This must blow their mind …

Ha yes, whenever someone who is shooting on film comes to my studio they realize that analog just isn’t old school enough.

How long did it take you to reach this point in your art, and where did you start?

It took me around three years to learn and successfully produce wet plate images here in Bali. I started by attending a few workshops in Europe and also learnt from the internet and vintage books from 19th century.

They are the best source of information but written in old funny language with some weird chemical units such as ‘drachms’ and ‘grains’. It’s been a really long and complicated journey.

Why do you do it?

For me it has become an obsession. There were many times I wanted to give up. The chemicals didn’t work, the image wouldn’t come up, or it would disappear after a few hours… It really is a lifelong journey. I am still at the very beginning.

What are you looking for in your subjects?

It is different every time. But with wet plate I focus on cultural and ethnic portraits with traditional costumes and classic portraits for private people.

Somehow this form seems to suit traditional Bali …

Yes I totally agree. That’s one of the reasons I really wanted to make it happen. It makes my subjects look as if they have come straight from 19th century. I love the ‘old Bali’ look.

What’s next for Stephan Kotas?

Right now I’m focusing on shooting wet plate portraits for private clients and art galleries. My next plan is to get my portable darkroom going. I don’t want to be restricted to working only in my studio; I want to be able to shoot on location in different parts of Bali. One of my biggest dreams is to go to Papua to shoot portraits in Baliem Valley. Bringing the wet plate process to the field is very challenging because of all the logistics, so any trip like this would replicate the hard core photo expeditions that took place in the old days. I will need to bring more than 100kg of equipment with me, a chemical lab and a darkroom. I am also starting to make platinum prints. It’s the most beautiful and also hardest contact print technique, producing long-lasting archival images. There’s only very few people in the world still doing it.

Best of luck in your adventures, Stephan.