Diana Darling reflects on a Bali that is fast disappearing. Did you miss the best of it?

If you came to Bali as a young thing in, say, 1976 (or in 1980, as I did), you would have seen things that you can’t capture in a selfie. You would have seen the movement of the invisible. But these days the old holy has become shy.

It used to flash out everywhere – at springs and by dusty roadsides, on stone steps, in magical drawings on cloth. It surged up through trees, bounced on fireflies, and glowed at the bottom of a dirty glass of arak. It danced in public. The Balinese were playful with the holy in those days, with their rough trance and bawdy ritual theatre. Their religion was an unselfconscious, multi-dimensional gorgeousness, which to the Balinese was just ordinary life.

Bali in the 1930s must have been a trip.

Now modern Balinese are becoming pious, and their religion is becoming a venue of identity politics. For the tourists, it’s wallpaper. The official face of Balinese culture is no longer a farmer but a grotesquely made-up dancer, often dancing for travel agents or guests of the government. The spontaneous magic and natural glamour of art performed for the gods now appears as just another entertainment item, before or after dinner. The ‘sacred’ is now a branding theme, applied to tour packages, spa treatments, cocktails.

Cultural tourism – conceived by prominent Balinese in the 1970s – was a strategy for somehow sharing their culture with tourists without ruining it. In those days, Balinese culture was a rural way of life with a peculiarly spectacular way of engaging with the spirit world. Then, slowly, what a tourist could see of the culture became obscured by the visual noise of new buildings and traffic jams; and the tourism product shifted from ‘culture’ to self-indulgence.

But life is like that: it keeps changing, and it tends to get worse as you grow old. Tourists have been complaining about the ruin of Bali since the 1930s. These days there is a generation of expatriates who remember the 1970s and ‘80s as a time when Bali was still infused with the old holy.

Things looked different then. Before the advent of cement blocks in Bali, people built their houses from what was on hand: stone and bamboo from the river gorge, mud bricks made in the back yard, and tough wild alang-alang grass for the roof. For Balinese, the ‘bathroom’ was the pigpen and the river. For foreigners, the bathroom was under the eaves, with a bin of water filled every day by a girl carrying a bucket on her head from the nearest stream.

This girl, your pembantu, did everything for you, because you yourself couldn’t carry water (or firewood or market produce) on your head. You didn’t know how to wash your clothes in the river. You rather felt like you couldn’t cook rice. Your pembantu would come to work at dawn and sweep the packed-earth yard around your house of the blossoms that had fallen in the night, and then spend the day cooking, laundering, doing your errands. But the main reason she was there was to make the daily offerings. She was probably the daughter or niece of your landlord, who was concerned about all the demons that would be attracted to the house of a foreigner. So she was there to keep harmony on the land. (Her doing everything else for you foreshadowed the pampering style of resort hospitality.)

In your little bamboo house, lighting was kerosene lamps that your pembantu cleaned and filled at the end of every afternoon, after sweeping up again before the swift fall of night. You listened to music on a little cassette player that ran on batteries. You also needed batteries for your torch, which you carried in a woven Dayak bag – along with a sarong and temple sash – whenever you left the house. You wrote on a little manual typewriter, or by hand.

Charlie Chaplin (left) with Walter Spies in Ubud…

Your bed was built of bamboo and it wobbled. The mattress was thin and lumpy, and had to be aired regularly by your pembantu. Your Chinese bed-linen from Singapore was baked fresh in the sun. If something really had to be ironed, your pembantu did it, of course, with an iron heated with burning charcoal. This sometimes scorched the cotton-rayon clothes that everyone wore and many expats designed.

The weather was always with you. Nowhere was truly indoors. In the hot dry months of September and October, the world was coated in fine dust. In the rainy season your feet were always wet, and your leather shoes (which you never wore except to go to Immigration) turned green with mould. Often in the rainy season you would be soaked to the skin in a sudden downpour. Then you would dry yourself at the fireplace in your kitchen, with a glass of muddy coffee, and wood smoke swirling in your hair.

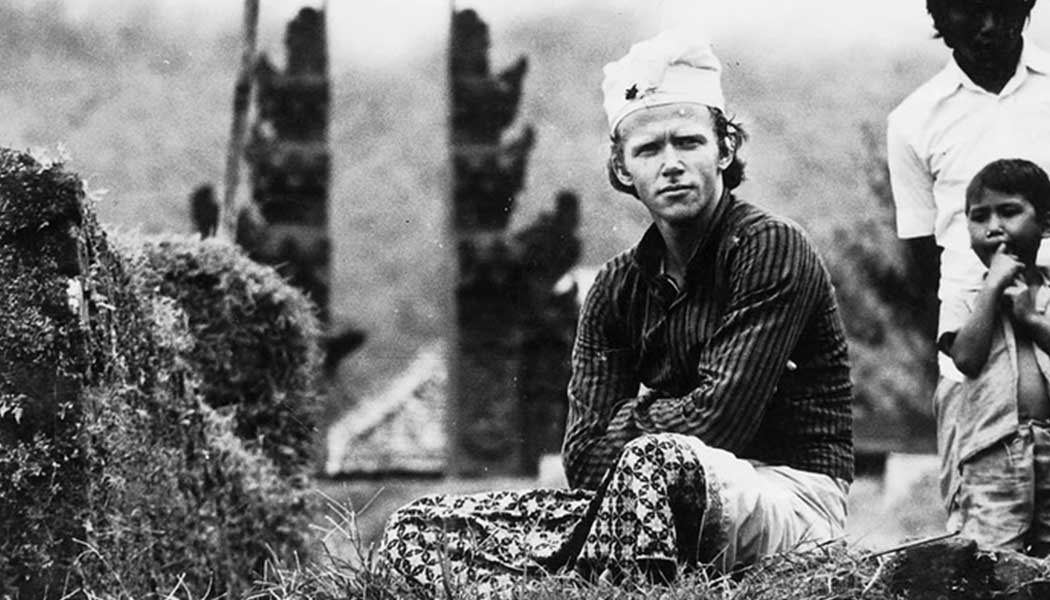

Legendary surfer Gerry Lopez in Bali. Photo: Tommy Schultz

In those days before telephones and fax, much less the internet, important business communications were conducted by telex at somebody’s office. But if you wanted to talk to anyone in Bali, you went to their house. To get there, you might walk along the beach or through Ubud and the occasional rice field. If it was far, you’d go by motorbike. If you had to go into Denpasar, you might take a bemo – a tiny truck with benches in the covered thing on the back – which plied vaguely defined routes and picked up anyone who waved it down. If your day in Denpasar was to be a busy one – say, the bank and then some shopping on Jalan Gajah Mada, then picking up airline tickets at the Bali Beach Hotel, followed by lunch at the Tandjung Sari – you might hire the bemo for the day for your private use and feel like a lord.

Photographer Leonard Lueras, here in Ubud, 1976, visited on R and R from Vietnam.

Time was slow in those early days, when nothing was truly comfortable or convenient and entertainment was scarce. People looked for the extraordinary in the subtle things around them. In your bamboo hut, you lived with the earth, amidst its smells and sounds. There was the sound of water running through ditches in the rice fields outside your house; the sucking sound of a buffalo pulling a plough through the mud, and the rattle of its wooden bell. There was massive birdsong in the morning, and the soft whooping of owls in the night, and the sound of wind rattling the leaves of coconut trees. The croaking of frogs was so large a feature of the night that the frog orchestra was a popular theme in the carving of wooden souvenirs and stone statuary, with each frog carrying a musical instrument. And you lived with the sky, ever alert to the weather and the time of day and the age of the moon. Would you get home before dark? Would there be enough moonlight to light your way?

In your sooty kitchen, you learned that the gods had resting places there – in the firewood rack above the stove, by the big terracotta water jug, in the rice basket – and your pembantu gave them little offerings every day after the cooking was done. She also put offerings at all the important points around the house where the invisible tended to cluster: by the gate, on the seat of your motorbike, on the ground in the middle of the well-swept yard, and on the little purpose-built shelf above your bed. Your landlord would have insisted that your house have its own temple, perhaps just a single shrine, before building began on the house itself. On certain days the offerings would be more elaborate and you might be encouraged to put off going to Denpasar for another, more auspicious day.

It was a time of oblivion about the rest of the world, partly imposed by Suharto’s military dictatorship which permitted only news that flattered it. International newspapers and magazines were censored and always out of date. Bank transfers and letters from your family took weeks to arrive. Sometimes you felt like you lived on another planet.

Yet it was a warm, voluptuous, and spacious planet. There was plenty of room for everything, and great freedom to move around in it. You could go anywhere you wanted, could drive up or down a street as you pleased and park at the door of wherever you were going, stop right outside the gates of a temple festival, where there was room for everyone to mill about in the ritual clutter. In the 1980s you could fly from Bali to Jakarta on a nearly empty DC-10, drinking whisky and smoking kreteks.

The late filmmaker and adventurer Lorne Blair … and friend.

In those days, only the main roads were paved, and if you stuck to them you’d never get lost anywhere on the island. You always had a view of Gunung Agung. On the coast, you could walk from your bedroom down a dirt track straight onto the beach.

And, if you liked, you could stroll along the beach completely naked, for this was also a time of astonishing personal liberty. The Balinese may have thought you were mad, or barbaric, but they didn’t appear to mind; or perhaps they were just too courteous to say anything. If you made a mess of yourself on magic mushrooms, they cleaned you up and called in a healer.

Very early on, there was a special relationship between the Balinese and the foreigners. It was not equitable, but it was collaborative and extremely fertile. This had much to do with the fact that, especially in the 1970s, Bali was very poor. Its economy was agrarian and its technology was neolithic. A decade earlier it had been devastated by mass killings and famine. And the national government, which permeated everything, promised that riches would be brought to Bali by international tourism – so foreigners were to be welcomed.

The early expats were not what the government had in mind, however. Indonesia was preparing (with great slowness) for a style of high-end tourism where visitors would stay in an enclave of five-star hotels, spend their dollars on souvenirs, and quickly be on their way. But in the 1970s, Bali was also a fabled destination on the hippie trail that extended from the Mediterranean through Afghanistan and India to Southeast Asia. It was about drugs and surfing and mysticism, and Bali was the jewel at the end of the rainbow.

These unanticipated visitors could hardly believe the glory of Kuta beach and its rolling surf and sunsets that soaked the world in red at the end of every day. And they were fascinated by the Balinese – by their beauty and dexterity, by their outlandish intimacy with the gods, by their fearless and tender care of the dead. Above all, they were delighted by their exuberant welcome. Whatever a wasted hippie might wish for, the impoverished Balinese competed to provide. A place to stay? Come stay at my house! A cold beer? We have the coldest! Or maybe you’d like me to climb a palm tree for a coconut? No problem!

Before long, foreigners and Balinese entered into a long love affair of many guises. Some of course were simply love affairs, and some resulted in marriages. Many of these produced little businesses, such as food stalls that catered to the tastes of surfers, hippies, and the growing tide of Australian students on holiday. Some grew into destination restaurants. The famous Made’s Warung took off in 1969 when the Dutchman Peter Steenbergen fell in love with the nubile Madé Masih, and they began serving food that foreigners craved, like bacon cheeseburgers and lemon sorbet soaked in vodka. Others saw the potential for producing handicrafts or jewellery or simple clothes. Or furniture. Or artwork in shells or glass. Or whatever. Some became rich in logistics businesses, exporting whatever people thought up to sell. Foreigners provided ideas and marketing, while Balinese provided labour and land. Investment cash came from wherever you could find it, and many Indonesians from outside Bali flocked to get in on the action.

Peter and Made at Made’s Warung, Kuta, 1974 … where it all started.

Expats in Kuta set the pace for going modern. They were the first to devise hot-water showers (say, from a coiled black hose on the roof of the bathroom), the first to design chic houses of timber and polished cement, the first to get air-conditioning, the first to venture into gastronomy. They partied hard at discotheques until breakfast time. Their Balinese partners opened petrol stations and supermarkets.

The scene in Sanur, on the other hand, was about gentility. Whereas Kuta’s expats were young and ardent, Sanur’s expats were sedate and exclusive; many lived in a park of private villas in Batujimbar. The focus of chic in Sanur was the Tandjung Sari hotel, which began as a few little huts on the beach, and whose brand evolved as bare-foot epicureanism for rock stars and royalty, in contrast to the hulking Hotel Bali Beach up the coast, whose main market was international sales conventions.

Made Wijaya aka Michael White, 1979. By Rio Helmi.

Hotels and expat houses in Sanur were large, fan-cooled bungalows and open-air pavilions surrounded by coral walls and masses of bougainvillea. Sanur’s most notorious expatriate was the Australian painter Donald Friend, who lived there in the 1960s and whose household was run, or perhaps overrun, by young boys. This idyll was perfected in the 1980s by the Australian landscape designer Made Wijaya. But aside from serving in houses or hotels, the native population of Sanur remained aloof from the foreigners, and devised their own, sometimes clueless, local restaurants and souvenir shops according to what they imagined the tourists wanted. They mostly kept to their own quiet way of life, their coral temples, and their discreet black magic.

Bemo Corner, 1978. Magic mushrooms not pictured.

Meanwhile in Ubud – which conceptually included the villages of Peliatan, Mas, Celuk, Batubulan, and Batuan – the tourism scene was all about ‘culture’. Already in colonial times, Ubud had been known to tourists as ‘the village of painters’ while Peliatan was ‘the village of dancers’, Mas ‘the village of woodcarvers’, Batubulan ‘the village of stone carvers’ and Celuk ‘the village of silversmiths’. Batuan was good at all these things. But the village of Ubud had the nous of marketing culture to tourists, thanks to the enthusiasm of Puri Ubud, its ruling family, for engaging with foreigners since the 1920s. Its most glamorous guest in those days was Walter Spies, the German painter, musician and amateur ethnographer who became the model for later generations of Ubud expats of how to ‘be’ in Bali – that is, you must be erudite in all things Balinese: the inscrutable multi-level language and peculiar calendars, the impossibly complicated music that made your heart ring like a bell. Visiting anthropologists found Ubud a good base from which to conduct their studies. The local people were used to foreigners and happy to elucidate what they understood from Puri Ubud to be Balinese culture.

In the 1970s, Ubud’s tourists were accommodated mostly in homestays, little huts in people’s backyards, which allowed visitors to participate in the life of the host family. The Balinese took pleasure in helping their guests put on traditional temple dress in order to fit in more respectfully with local religious ceremonies, and both sides did their best to understand each other’s strange cultures. Lasting friendships often arose, and of course businesses, too. Perhaps the most exemplary of these is Threads of Life – an endeavour started by Jean Howe and her husband William Ingram, with the help of I Wayan Sudarta – which is devoted to indigenous textile traditions of Indonesia. The friendship perhaps began when Jean saw the ghost of Sudarta’s late father sitting in the family courtyard.

No matter where they were, Bali’s expats of the 1970s, ‘80s and even ‘90s seemed to ride a tsunami of success. This was a time when if you had an idea, you could carry it out. Start something, design something, build something, stage something. Creativity was burgeoning, and everywhere there were bright young Balinese to help you turn it into a business project. The Balinese were caught up in the excitement. They contributed their talent and their connections, their genius for teamwork. Jewellers and woodcarvers and dancers and builders brought the knowledge they’d inherited about the old way of doing things and an eagerness to do things in a fresh new way – and make money!

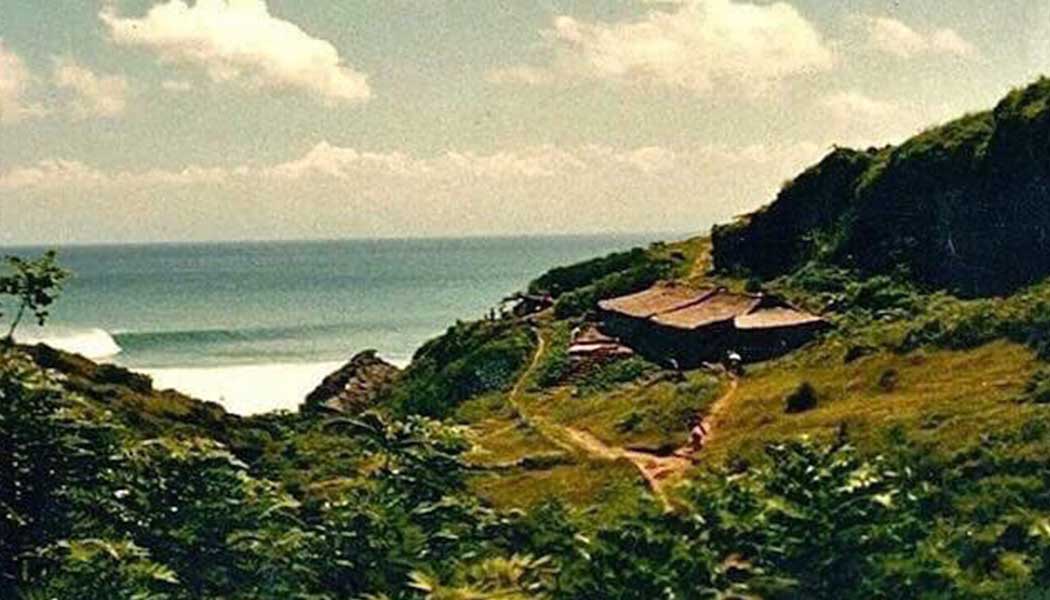

Uluwatu, mid 1980s.

For this was also a time when money was surging into the island. Everything multiplied – the population, the tourist arrivals, the hotels and artshops, the banks, the villas, the malls and spas and gourmet shops and car dealerships – and urban Bali is now almost choking on money. The only thing that has not multiplied is the land, but there are plans for that.

In this newly rich and crowded world, the Balinese see money as the metric of success, even a virtue: if it makes money it must be good. Yet the people of Bali have not lost their bearings, nor their memory of poverty. Money – a new form of life’s abundance – is gratefully recycled back to the gods in religious ceremonies, always on a scale beyond their means. Ritual extravagance is a sign of devotion. And big ceremonies make a point about Hindu pride.

Yet to some outsiders, excess and the holy do not go together. Foreigners have always had their own notions about what Bali should be; in general, they think Bali should be the way it was when they first got there. Some foreigners today feel that the Balinese should be spending their new wealth on education, health care, waste management, low-impact public transport, and animal welfare shelters.

But the Balinese have always known how to manage the universe. The difference between now and then is that in the olden days, the entire universe seemed to fit into the little world that was Bali, and to us the fit looked perfect.

Click here to read more about old Bali … and the people who experienced it.