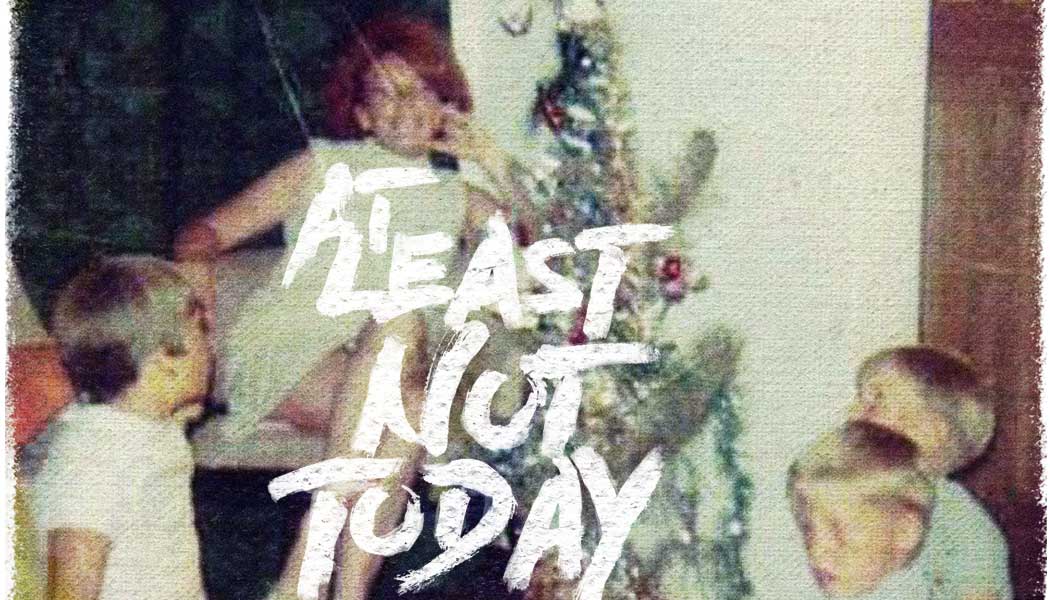

Gava Fox reflects on a mother’s love as he looks back on times good and bad.

My mother died last year and, to my eternal shame, it came as a blessed relief.

My father passed away 12 years earlier, and that was a shock.

In the middle of the night, as he slept, he suffered a massive stroke, and less than 48 hours later died without gaining consciousness.

My mother, however, lingered at death’s door for years – stubbornly defying the doctors who told us in 2009 that she had only months to go.

She was a bright and vibrant beauty in her day, the queen of trivia who could beat everyone at Scrabble and do a crossword faster than anyone she knew.

She read voraciously – although in later years became darkly fascinated by the true crime genre – and even in her seventies enjoyed nothing more than a glass of Baileys and a sneaky cigarette to watch the Zimbabwe sun go down.

But then she started “losing it”.

At first, shamefully, we accused her of being selfish, trying to grab the spotlight when her four young granddaughters had become the centre of attention.

She’d constantly repeat herself, forget even the simplest things and make inappropriate comments to strangers.

Finally, we got a proper diagnosis. She was suffering from Pick’s disease, the specialist said, which had us heading to the medical textbooks.

“Pick’s disease has a rapidly progressing insidious course with steady deterioration and fatality generally occurring (on average) four years from diagnosis,” we read. “No known cure exists.”

She came and stayed with me for a couple of months in Singapore for one last hurrah, oblivious to our plans to put her in a dementia home, as doctors recommended.

That visit was bittersweet.

Frequently she was lucid, more than holding her own in conversations with my friends over a long lunch, but the next day she could be a complete stranger.

Sometimes her actions were so shocking, you just had to laugh.

One day at work I received an urgent call from the security guard at my condominium asking me to return immediately. When I got home, mum was paddling in the shallow end of the communal swimming pool, stark naked, the residents desperately trying to avoid looking.

A few weeks later she announced she was off to the corner shop to buy some cigarettes, clad only in her bra and knickers.

Although she had spent most of her life in Africa, we managed to find her a place at a home near Birmingham, in Britain, just a mile or so from where she was born.

My sister, bless her, also moved to the UK to be nearby.

Mum was miserable at first, pleading with us to take her home whenever we’d visit, but she was deteriorating fast and soon had no idea where she was.

By coincidence, the sheltered accommodation had several nurses and helpers from Zimbabwe working there – escapees from the country’s economic malaise – and so in time mum forgot she was in the UK and became convinced she was back in Africa.

When she settled in, she at first ruled the place like the lady of the manor. She was still quite mobile, and liked nothing more than a stroll in the gardens for an afternoon cigarette.

We could even take her out for a lunch at a village pub, although after a few hours you could tell she was getting anxious and wanted to return.

But her condition deteriorated fast.

Within a couple of years she was no longer mobile and had to be lifted out of bed into a wheelchair. Within months she was no longer capable of using a knife and fork and had to be spoon fed by immensely patient helpers.

There was still a twinkle in her eyes when you visited, however, even if her vocabulary had been reduced to a few words.

On one of my last visits, she confused me with my brother – attempting a smile but repeating his name as she gamely clasped my hand.

My brother stopped taking his daughters to see her. He wanted them to remember her when she was full of life, not the hollow shell that she’d become.

And I dreaded visiting too.

The last time I did, it broke my heart. There wasn’t even a flicker of recognition. She couldn’t say a word and just sat in her wheelchair, head slumped, drooling.

I left after 15 minutes.

I had to go for a long walk, in turns berating myself for not having the courage to give her more of my time, and feeling sorry for myself for being put in this position.

Last year, a few months before I had planned to visit again, I got a long-awaited – but not dreaded – call from my sister to say mum had slipped into a pneumonia-related coma from which she was not expected to recover. Doctors gave her just hours, and this time they were right.

There would still be one final indignity, however.

In her final hours she had been moved from the dementia home to a local hospital, and as a result there would have to be a full coroner’s inquiry into the cause of death.

The state of Britain’s non-emergency national health system is such these days that it would take nearly two months before that could be done, and her body released.

This month – May 12 to be precise – is celebrated around the world as International Mother’s Day, although Britain stubbornly clings to the fourth Sunday of March to mark the date.

We all have mothers, even if some of us are not fortunate enough to get to know them.

Nowhere in modern fiction, perhaps, is motherhood given as much prominence as in the hit current TV series Game of Thrones – particularly given the claims of various illegitimate offspring to the myriad ruling houses competing for the sword-forged Iron Throne.

Daenerys Targaryen, one of the main characters and arguably one of the good guys, is known as the “Mother of Dragons” having hatched three of the beasts by walking through fire.

Cersei Lannister, a definite baddie, has no doubt been made worse by the deaths of three of her offspring for whom she schemed endlessly over the course of the series.

In many cultures, the worst insult you can hurl at an enemy is to insult their mother – seeing red can often, literally, be the result.

In 2004, playing for Real Madrid, David Beckham thought he had tackled Real Murcia’s Luis Garcia cleanly, but the linesman flagged for a foul.

Enraged, the England captain unleashed his entirety of Spanish at the official, calling him a hijo de puta (son of a whore). The referee went straight to his pocket and produced a red card.

“I didn’t realise what I had said was that bad. I had heard a few of my team mates say the same before me,” was Beckham’s defense.

In an even more controversial case, French captain Zinedine Zidane was sensationally sent off in the 2006 World Cup final after head-butting Marco Materazzi when the Italian called him the “Son of a prostitute”.

Reduced to 10 men, France lost a final they were widely expected to win.

Even Pope Francis has weighed in on the mother issue.

The Catholic Church, of course, elevates motherhood to a holy pinnacle, with Mary, the mother of Jesus, venerated as a primary saint.

In a discussion of freedom of expression in 2015, Pope Francis defended the rights of individuals to hold contrary opinions, but warned against one particular train of thought.

“Curse my mother, expect a punch,” said Francis. “It’s normal . . . you cannot provoke.”

While motherhood is cherished around the world, not everyone makes a good mother – although it is the exception rather than the rule.

Take the case of Mary Ann Cotton, for example.

The 19th Century nurse poisoned and killed 11 of her 13 children, all four of her husbands and two lovers – all for their insurance money.

The Times reported she still hoped for a royal pardon after conviction, but was hanged in 1873 and died not from her neck breaking, but by strangulation caused by the rope being cut too short – possibly deliberately.

In her memoir Mommie Dearest, Christine Crawford details how she was treated cruelly by her adoptive mother, the Hollywood superstar actress Joan Crawford, who used her as a career-boosting accessory.

Turned into a hit Hollywood movie starring Faye Dunaway in the title role, it describes the author’s upbringing by an unbalanced alcoholic mother and attracted much controversy regarding child abuse and trafficking.

This month I’ll think back with a great deal of regret, a great deal of gratitude and a great deal of love for the woman who was my mother.

Hopefully some time later this year, the three of us – her children – along with various grand children, and friends, will gather in Zimbabwe to scatter mum’s ashes in a place she loved.

For those of you who still have your mums around, enjoy them while you can.

Gava Fox is a writer, editor and former war correspondent. Read more from him here.