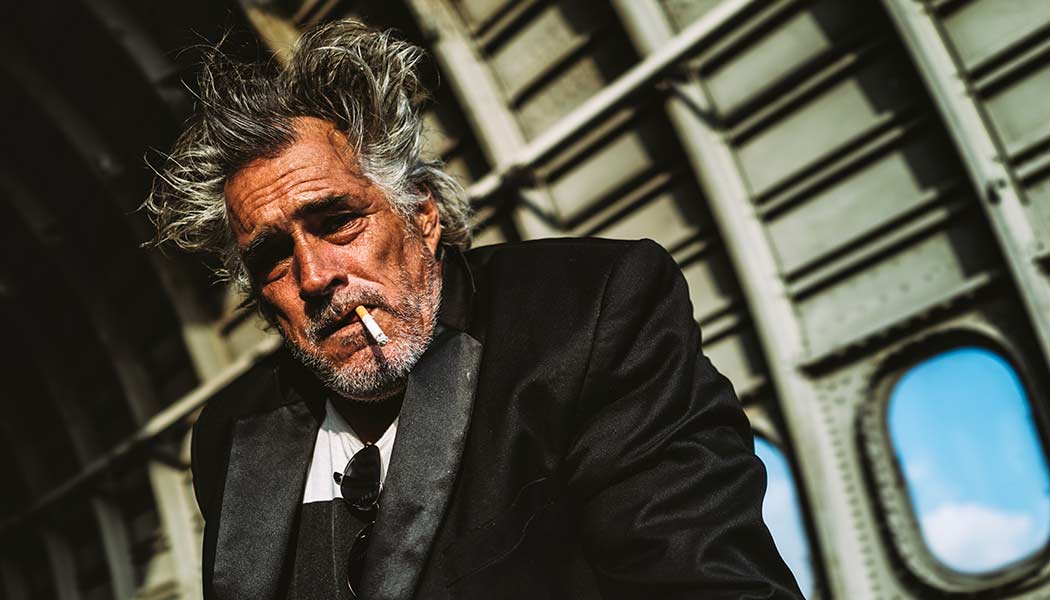

Skateboard pioneer Steve Olson is still breaking the rules. Words: Luiz Sanchez. Photos: Jason Reposar at Gate 88.

Skateboarding played a formative experience in my life. Granted I couldn’t drop in a vert to save my life, and my greatest claim to fame was nearly landing a kickflip one time, but the better half of my teenage years were spent cruising up and down Rotterdam with my friends. We would skate tunnels and train stations, running from the cops whenever our antics caught their ire. We would get drunk, high, occasionally tag buildings and explore the city in search of new places to skate. There was something primal about skateboarding, something rebellious. There still is. In a world full of rules and responsibilities, skateboarding allowed us tiny moments of freedom.

When I was given the chance to interview Steve Olson I nearly lost my shit. The Steve Olson? The dude who married the punk scene to skateboarding? THE guy that has definitely seen it all? Hell yeah.

I knew Steve’s story, it’s been written and rewritten dozens of times. Growing up in California Steve was a prolific surfer before ever setting foot on a skateboard. By age 16 he was already established as a competitive skater. Growing up in California in the ’70s meant getting creative, as skateparks weren’t a thing and youngsters like Steve would scour the suburbs looking for construction sites and empty swimming pools to skate.

I met him at Beach Garden – In the Raw in Canggu, as the sun neared its zenith. As we sat down for the interview he got a call and took a moment before the meeting. “Sorry about that,” he said hanging up. “We filmed a skateboarding short in Paris in July.”

A friend had invited him to Paris to paint with him. “I was there painting and skating and trying to immerse myself in Paris to get the vibe of the city. When I was there I met some good dudes and had an idea. We all have phones, let’s shoot a short on them. It’s just a basic idea but basic ideas are powerful. The Pusher is Steve’s attempt to catch the essence of skateboarding. “It’s a passing of the torch from an older guy to a younger kid.”

It’s an apt motif. Having met and been friends with virtually every legendary skater from the ’70s onwards, Steve has consistently been at the frontline of skateboarding. He’s seen the sport grow from sidewalk surfing and pool skating to the modern-day mainstream meganaut it has become. He has seen the equipment evolve from surfboard analogues with clay wheels to contemporary variants.

“I was born in the early ’60s,” he says. “I was influenced by longboarding and surfing. In the mid-60s a lot of the skaters were surfers and it was huge. Skating became extremely popular in a very trendy sort of way . . . like the hoola hoop.”

Despite its popularity, skating took a dive in ’66 as moral panic sought to restrict the burgeoning sport until ’72, when polyurethane wheels were introduced. “It was groundbreaking,” Steve explained. “The polyurethane wheels gave you a smoother ride, it was quieter, definitely had a faster roll and gave you much more traction when turning.”

“In the late ’70s they had a pool competition called the Hester Series and it kind of seemed at that point to provide a proving ground for anyone who wanted to compete. It was the first of its kind and we thought let’s go, it’s on. I knew how to compete and did extremely well. In the competitive scene you had to do tricks. You were trying to up your competitors and I could do that, we could skate. The crazy thing is there were new generations happening within six months of each other. Not every five years or every year, it was happening so fast. Tricks and wheels were getting better, boards got wider, then Bobby Valdez did an invert in 1978 and everything caught on fire. I had to learn airs or I’d have fallen behind.

“This kid from Florida, Alvan Galvin, came in after the first competitions and showed us what the ollie was [now a basic skateboard jump] and that was mind blowing, totally,” Steve recounted. “I mean, watch this little alien pop, and he had a really cool, funky, bizarre style from the other guys, it was wow, this is getting really wild.”

In 1979 Steve was awarded Skateboarder of the Year by Skateboarder Magazine. “I remember I wore leather pants, a white blazer, some ridiculous polka dot tie and shoes that were way too tight but too cool not to be seen, and I remember they get to the top 10 and I heard the names of my friends and I remember thinking wow, I didn’t even make it to the top 10. Tony Alva had won the year before and he came in second place. He was pissed and threw his trophy in the trash, which I thought was fantastic. Then they said the Skateboarder of the Year is . . . Steve Olson. I was totally blown away but at the same time I had been drinking and thought all these people didn’t understand the scene happening in my world.”

“I remember them saying speech speech speech and I thought whatever,” Steve says. “I remember spitting at the camera, picking my nose, flicking boogers at them and giving them the finger. And it wasn’t to the kids into skateboarding, it was against the industry and the squares. Go fuck yourselves. They said these two guys were the worst representation of skateboarding but the kids just totally understood. They were like oh, what do you mean? These guys were saying fuck yourselves, they were skateboarding for the matter and the kids jumped on our side and it was fantastic. And then it died.”

At the height of skateboarding’s popularity, the US economy hit a downturn. The recession, coupled with lawsuits, resulted in the closure of most skateparks across the country. Skateboard magazines began to fold or morph into general sports magazines to attract wider audiences. But while skateboarding never truly went away, the opportunity to make a living out of it certainly shrank. “We kept skateboarding because it wasn’t about that it was more about digging it,” Steve explained. “A lot of us kept skating . . . but the business died. A couple of companies survived but so many companies closed. Alright now what do you do? One year you’re on top of everything and the next year they’re sayin’ . . . now what are you gonna do with your life? Fuck I don’t know, I was blown away by the sport,” he said. “I still am.”

This is Steve’s second trip to Bali. The first time he was here was back in the late ’80s, on the eve of Bali’s transition to a major tourist destination. “I brought a skateboard, dunno why, there was only one road in Kuta that was freshly paved and well done,” he recalled. I remember I came and put my shit away at the hotel and looked for my friend Mark Baker. So I’m skating down this street in Kuta and these little kids were tripping so I was like here try it. They were having such a good time I told them to keep the board. I love Bali. It’s been 30 years, it’s changed but I just love Bali. One of the best things is to hop on your scooter and just go. You have to be on guard and paying attention but it’s amazing, just throw your surfboard on the rack and go.”

“I’m all about supporting the skate scene here,” Steve says. “They see a different style of skateboarding when I skate, because it’s still surfing for me. I don’t really care about tricks, I care about power, and turning, slashing and grinding.”